Experiential Quests into Past Lives

Bridey murphy

To a great number of Americans, the name Bridey Murphy has become synonymous with reincarnation and accounts of past lives. The story of the Pueblo, Colorado, housewife who remembered a prior incarnation as a nineteenth-century Irish woman while under hypnosis made a dramatic impact upon the public imagination. Newspapers, magazines, and scholarly journals debated the validity of the "memory," and the controversy surrounding this alleged case of reincarnation has not resolved itself to this day.

William J. Barker of the Denver Post published the first account of this now-famous case in that newspaper's Empire magazine. Barker told how Morey Bernstein, a young Pueblo business executive, first noticed what an excellent subject "Mrs. S." was for deep trance when he was asked to demonstrate hypnosis at a party in October of 1952. It was some weeks later, on the evening of November 29, that Bernstein gained the woman's consent to participate in an experiment in age-regression.

The amateur hypnotist had heard stories of researchers having led their subjects back into past lives, but he had always scoffed at such accounts. He had been particularly skeptical about the testimony of the British psychiatrist Sir Alexander Cannon, who reported that he had investigated over a thousand cases wherein hypnotized individuals had recalled past incarnations.

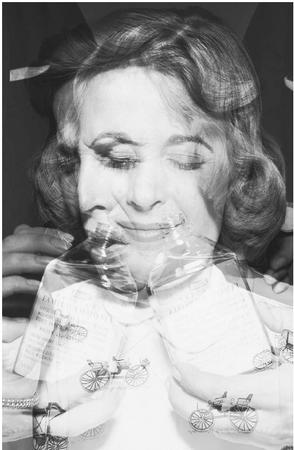

Mrs. S., who later became identified as Ruth Simmons (and many years later by her actual name, Virginia Tighe), was not particularly interested in hypnotism, either, nor in becoming a guinea pig for Bernstein's attempt to test the theses of those psychical researchers who had claimed the revelation of past lives. She was, at that time, 28 years old, a housewife who enjoyed playing bridge and attending ball games with her husband.

With Rex Simmons and Hazel Bernstein as witnesses, the hypnotist placed Simmons in a trance and began to lead her back through significant periods of her childhood. Then he told her that she would go back until she found herself in another place and time and that she would be able to talk to him and tell him what she saw. She began to breathe heavily and her first words from an alleged previous memory were more puzzling than dramatic. She said that she was scratching the paint off her bed because she was angry over having just received an awful spanking. She identified herself by a name that Bernstein first heard as "Friday," then clarified as "Bridey," and the

Bridey—short for Bridget—Murphy began to use words and expressions that were completely out of character for Ruth Simmons. Bridey told of playing hide'n'seek with her brother Duncan, who had reddish hair like hers (Simmons was a brunette). She spoke of attending Mrs. Strayne's school in Cork where she spent her time "studying to be a lady." With sensitivity she recreated her marriage to Brian MacCarthy, a young lawyer, who took her to live in Belfast in a cottage back of his grandmother's house, not far from St. Theresa's Church.

In her melodic Irish brogue, Bridey told of a life without children, a life laced with an edge of conflict because she was Protestant while Brian was Catholic; then in a tired and querulous voice, she told how she had fallen down a flight of stairs in 1864 when she was 66. After the fall, she was left crippled and had to be carried about wherever she went.

Then one Sunday while her husband was at church, Bridey died. Her death upset Brian terribly, she said. Her spirit lingered beside him, trying to establish communication with him, trying to let him know that he should not grieve for her. Bridey told the astonished hypnotist and the witnesses that her spirit had waited around Belfast until Father John, a priest friend of her husband's, had passed away. She wanted to point out to him that he had been wrong about purgatory, she said, and added that he admitted it.

The spirit world, Bridey said, was one in which "you couldn't talk to anybody very long…they'd go away." In the spirit realm, one did not sleep, never ate, and never became tired. Bridey thought that her spirit had resided there for about 40 Earth years before she was born as Ruth Simmons. (Ruth/Virginia had been born in 1923, so Bridey's spirit had spent nearly 60 years in that timeless dimension.)

At a second session, Bridey again stressed that the afterlife was painless, with nothing to fear. There was neither love nor hate, and relatives did not stay together in clannish groups. Her father, she recalled, said he saw her mother, but she hadn't. The spirit world was simply a place where the soul waited to pass on to "another form of existence."

Details of Bridey Murphy's physical life in Ireland began to amass on Morey Bernstein's tape recorders. Business associates who heard the tapes encouraged Bernstein to continue his experiments, but to allow someone else, a disinterested third party, to check Bridey's statements in old Irish records or wherever such evidence might be found. Ruth Simmons was not eager to continue, but the high regard that she and her husband had for Bernstein led her to consent to additional sessions.

Utilizing her present-life incarnation as Ruth Simmons, Bridey Murphy demonstrated a graceful and lively rendition of an Irish folk dance which she called the "Morning Jig." Her favorite songs were "Sean," "The Minstrel's March," and "Londonderry Air." Ruth Simmons had no interest in musical activities.

William Barker of the Denver Post asked Bernstein if the case for Bridey Murphy could be explained by genetic memory which had been transferred through Simmons's ancestors, for she was one-third Irish. Bernstein conceded that such a theory might make the story more acceptable to the general public, but he felt the hypothesis fell apart when it is remembered that Bridey had no children. He also pointed out that other researchers who have regressed subjects back into alleged previous-life memories have found that blood line and heredity have nothing to do with former incarnations. Many have spoken of the afterlife as a kind of "stockpile of souls." When a particular type of spirit is required to inhabit and animate a body that is about to be born, that certain spirit is selected and introduced into that body. Bernstein observed that a person who boasts of having noble French ancestry might have been a slave or a concubine on his or her prior visit to the physical plane of existence.

In Bernstein's opinion, one could take only one of two points of view in regard to the strange case of Bridey Murphy. One might conclude that the whole thing had been a hoax without a motive. This conclusion would hold that Ruth Simmons was not the "normal young gal" she appeared to be, but actually a frustrated actress who proved to be a consummate performer in her interpretation of a script dreamed up by Bernstein because he "likes to fool people." Or if one did not accept that particular hypothesis, Bernstein said, then the public must admit that the experiment may have opened a hidden door that provided a glimpse of immortality.

Doubleday published Morey Bernstein's The Search for Bridey Murphy in 1956. Skeptics and serious investigators alike were interested in testing the validity of Bernstein's experiments and in determining whether or not they might demonstrate the reality of past lives.

In mid-January of 1956, the Chicago Daily News sent its London representative on a three-day quest to check out Cork, Dublin, and Belfast and attempt to uncover any evidence that might serve as verification for the Bridey Murphy claims. With only one day for each city, it is not surprising that the newsman reported that he could find nothing of significance.

In February, the Denver Post sent William Barker, the journalist who first reported the story of the search for Bridey Murphy, to conduct a thorough investigation of the mystery. Barker felt that certain strong supportive points had already been established by Irish investigators and had been detailed in Bernstein's book. Bridey (Irish spelling of the name is Bridie) had said that her father-in-law, John MacCarthy, had been a barrister (lawyer) in Cork. The records revealed that a John MacCarthy from Cork, a Roman Catholic educated at Clongowes School, was listed in the Registry of Kings Inn. Bridey had mentioned a "green-grocer," John Carrigan, with whom she had traded in Belfast. A Belfast librarian attested to the fact that there had been a man of that name and trade at 90 Northumberland during the time in which Bridey claimed to have lived there. The librarian also verified Bridey's statement that there had been a William Farr who had sold foodstuffs during this same period. One of the most significant bits of information had to do with a place that Bridey called Mourne. Such a place was not shown on any modern maps of Ireland, but its existence was substantiated through the British Information Service.

While under hypnosis, Ruth Simmons had "remembered" that Catholics could teach at Queen's University, Belfast, even though it was a Protestant institution. American investigators made a hasty prejudgment when they challenged the likelihood of such an interdenominational teaching arrangement. In Ireland, however, such a fact was common knowledge, and Bridey scored another hit. Then there were such details as Bridey knowing about the old Irish custom of dancing at weddings and putting money in the bride's pockets. There was also her familiarity with the currency of that period, the types of crops grown in the region, the contemporary musical pieces, and the folklore of the area.

When Barker dined with Kenneth Besson, a hotel owner who was interested in the search, the newsman questioned Bridey's references to certain food being prepared in "flats," an unfamiliar term to Americans. Besson waved a waiter to their table and asked him to bring some flats. When the waiter returned, Barker saw that the mysterious flats were but serving platters.

Some scholars believed that they had caught Bridey in a gross error when she mentioned the custom of kissing the Blarney Stone. Such a superstition was a late nineteenth-century notion, stated Dermot Foley, the Cork city librarian. Later, however, Foley made an apology to Bridey when he discovered that T. Crofton Cronker, in his Researches in the South of Ireland (1824), mentions the custom of kissing the Blarney Stone as early as 1820.

Bridey was correct about other matters that at first were thought to be wrong by scholars and authorities. For example, certain authorities discredited her statement about the iron bed she had scratched with her fingernails after the "awful spanking" on the grounds that iron beds had not yet been introduced into Ireland during the period in which Bridey claimed to have lived. The Encyclopedia Britannica, however, states that iron beds did appear in Bridey's era in Ireland and were advertised as being "free from the insects which sometimes infect wooden bedsteads." Bridey's claims to have eaten muffins as a child and to have obtained books from a lending library in Belfast were at first judged to be out of proper time context. Later, her challengers actually uncovered historical substantiation for such statements.

Throughout the regressions conducted by Morey Bernstein, one of the most convincing aspects of the experiments had been the vocabulary expressed by the hypnotized subject. The personality of Bridey Murphy never faltered in her almost poetic speech, and of the hundreds of words of jargon and colloquial phrases she uttered, nearly all were found to be appropriate for the time in which she claimed to have lived. The songs that Bridey sang, her graphic word pictures of wake and marriage customs, were all acclaimed by Irish folklorists as being accurate. Her grim reference to the "black something" that took the life of her baby brother probably referred to famine or disease. The Irish use of "black" in this context means "malignant" or "evil" and would have nothing to do with the actual color of the pestilence.

Bridey Murphy did not always score hits, though. Numerous Irish historians and scholars felt that she must have been more Scottish than Irish, especially when she gave the name Duncan for her father and brother. Certain experts sympathetically suggested that she may have been attempting to say Dunnock, rather than Duncan.

William Barker could find no complete birth data for either Bridey or her kin, and he learned that she had shocked most Irish researchers with her crude term "ditched" to describe her burial. The Colorado journalist was informed that the Irish are much too reverent about the dead to employ such a brutal word.

Bridey demonstrated little knowledge of Ireland's history from 1800 to 1860. Bridey and Brian's honeymoon route was hopelessly untraceable and appeared to be confused with the trip that she had made to Antrim as a child of 10. The principal difficulty in accepting the whole of Bridey's story lay in the fact that so much of the testimony was unverifiable.

While most psychical researchers agree that the Bridey Murphy case is not a consciously contrived fraud, they will not rule out the role that some psychic or extrasensory ability may have played in the "memory" of the Irish woman allegedly reborn in a Colorado housewife. Other investigators have suggested that Mrs. S., Virginia Tighe, could have had several acquaintances throughout her life who were familiar with Ireland and who may each have imparted a bit of the memory of Bridey Murphy as it was mined from her subconscious by the hypnotic trance induced by Morey Bernstein.

As other researchers explored the claims of The Search for Bridey Murphy, the phenomenon of cryptomensia was also applied to the case when reporters for the Chicago American discovered that a woman named Bridie Murphey Corkell had lived across the street where Virginia Tighe had grown up. To say that cryptomensia was responsible for Tighe's alleged memories of a nineteenth-century Irish-woman is to propose that she had forgotten both the source of her "memory" and the fact that she had ever obtained it. Then, under hypnosis, such memories could be recalled so dramatically that they could be presented as a past-life memory.

The attempts to discredit Bridey Murphy as a manifestation of cryptomensia fail in the estimation of researchers C. J. Ducasse and Dr. Ian Stevenson (1918– ). In Stevenson's estimation, the critics of the Bridey Murphy case provided only suppositions of possible sources of information, not evidence that these had been the sources.

The controversy over Bridey Murphy and the value of past-life regressions still rages. Those who champion the case state that it cannot be denied that Bridey/Virginia possessed a knowledge of nineteenth-century Ireland that contained a number of details that were unfamiliar even to historians and authorities. Such details, when checked for accuracy after elaborate research, were found to be correct in Bridey's favor. Others insist that such data could have been acquired paranormally, through extrasensory means, and therefore does not prove reincarnation. Skeptics dismiss the evidence of Bridey Murphy's alleged past-life memories by stating that they originated in her childhood, rather than in a prior incarnation.

On July 12, 1995, Virginia Tighe Morrow died in her suburban Denver home. She had never again submitted to hypnosis by any researcher seeking to test her story. Although she never became a true believer in reincarnation, she always stood by the entranced recollections as recorded in The Search for Bridey Murphy.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: