How the Major Religions View the Afterlife

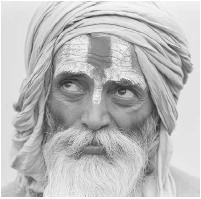

Hinduism

In India's religious classic work, the Bhagavad Gita ("Song of the Lord"), the nature of the soul is defined: "It is born not, nor does it ever die, nor shall it, after having been brought into being, come not to be hereafter. The unborn, the permanent, the eternal, the ancient, it is slain not when the body is slain."

The oldest collection of Sanskrit hymns is the Rig-Veda, dating back to about 1400 B.C.E. Composed by the Aryan people who invaded the Indus Valley in about 1500 B.C.E., the early Vedic songs are primarily associated with funeral rituals and perceive the individual person as composed of three separate entities: the body, the asu (life principle), and the manas (the seat of the mind, will, and emotions). Although the asu, and the manas were highly regarded, they cannot really be considered as comprising the essential self, the soul. The facet of the person that survives the physical is yet something else, a kind of miniature of the living man or woman that resides within the center of the body near the heart.

During the period from about 600 B.C.E. to 480 B.C.E., the series of writings known as Upanishads set forth the twin doctrines of samsara (rebirth) and karma (the cause and effect actions of an individual during his or her life). An individual has a direct influence on his or her karma process in the material world and the manner in which the person deals with the difficulties inherent in an existence bound by time and space; the individual determines the form of his or her next earthly incarnation. The subject of the two doctrines is the atman, or self, the essence of the person that contains the divine breath of life. The atman within the individual was "smaller than a grain of rice," but it was connected to the great cosmic soul, the Atman or Brahma, the divine principle. Unfortunately, while occupying a physical body, the atman was subject to avidya, an earthly veil of profound ignorance that blinded the atman to its true nature as Brahma and subjected it to the processes of karma and samsara. Avidya led to maya the illusion that deceives each individual atman into mistaking the material world as the real world. Living under this illusion, the individual accumulates karma and continues to enter the unceasing process of samsara, the wheel of return with its succession of new lifetimes and deaths.

The passage of the soul from this world to the next is described in the Brihadarankyaka Upanishad:

The Self, having in dreams enjoyed the pleasures of sense, gone hither and

By the third century B.C.E. Hinduism had largely adopted a cyclical worldview of lives and rebirths in which the earlier concepts of heaven and hell, an afterlife system of reward and punishment, were replaced by intermediate states between lifetimes. Hindu cosmology depicted three lokas, or realms—heaven, Earth, and a netherworld—and 14 additional levels in which varying degrees of suffering or bliss awaited the soul between physical existences. Seven of these heavens or hells rise above Earth and seven descend below. According to the great Hindu teacher Sankara, who lived in the ninth century, and the school of Advaita Vedanata, the eventual goal of the soul's odyssey was moksa, a complete liberation from samsara, the cycle of death and rebirth, which would lead to nirvana, the ultimate union of atman with the divine Brahma. In the eleventh century, Ramanjua and the school of Visitadvaita saw the bliss of nirvana as a complete oneness of the soul with God.

In the last centuries before the common era, a form of Hinduism known as bhakti spread rapidly across India. Bhakti envisions a loving relationship between God and the devout believer that is based upon grace. Those devotees who have prepared themselves by a loving attitude, a study of the scriptures, and devotion to Lord Krishna may free themselves from an endless cycle of death and rebirth. Eternal life is granted to the devotees who, at the time of death, give up their physical body with only thoughts of Lord Krishna on their minds.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: