THE MODERN UFO ERA BEGINS

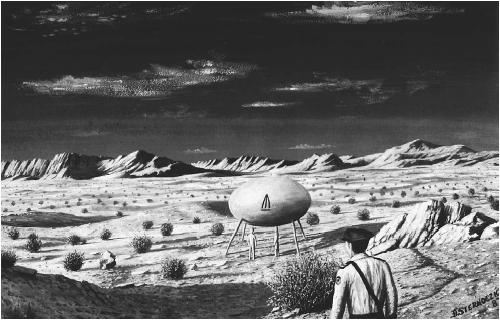

After takeoff from the Chehalis, Washington, airport in his personal plane on June 24, 1947, Kenneth Arnold headed for Yakima, Washington. As he flew directly toward Mount Rainier at an altitude of approximately 9,500 feet, a bright flash reflected on his airplane. To the left and north of Mount Rainier he observed a chain of nine peculiar-looking objects flying from north to south. They were approaching Mount Rainier rapidly, and he assumed that they were jet aircraft. Every few seconds two or three of the objects would dip or change course slightly, just enough for the sun to reflect brightly off

After numerous sightings of unidentified flying objects had been reported by commercial and military pilots and an alleged flying saucer had crashed outside of Roswell, New Mexico, in early July 1947, army air force pilots were reminded of the weird "foo fighters" that several Allied personnel had seen in World War II (1939–45). Often while on bombing missions, crews noticed strange lights that followed their bombers. Sometimes the "foos" darted about. Other times they were seen to fly in formation. Barracks and locker-room rumors had classified the "foo fighters" as another of the Nazis' secret weapons, but not a single one of the glowing craft was ever shot down or captured. Neither is there any record of a "foo" ever damaging any aircraft or harming any personnel—outside of startling the wits out of pilots and crew members.

The "foos" were spotted in both the European and Far Eastern theaters, and it came as no surprise to these pilots when waves of "foos" were sighted over Sweden in July 1946. A kind of hysteria gripped Sweden, however, and the mysterious "invasion" was reported at great length in the major European newspapers. Some authorities feared that some new kind of German "V" weapon had been discovered and unleashed on the nation that had remained neutral throughout World War II. Others tried to explain the unidentified flying objects away as meteors, but witnesses said that the "ghost rockets" could maneuver in circles, stop and start, and appeared to be shaped like metal cigars.

It may have been an air force officer who remembered the "foo fighters" who gave the

The hostile order was withdrawn on White House orders by five o'clock that afternoon. That night, official observers puzzled over the objects, visible on radar screens and to the naked eye, as the UFOs easily outdistanced air force jets, whose pilots were ordered to pursue the objects but to keep their fingers off the trigger. Although the air force was denying the Washington flap within another 24 hours and attributing civilian saucer sightings to the usual causes (hallucinations, seeing planets and stars), the national wire services had already sent out word that for a time the air force officials had been jittery enough to give a "fire at will" order.

On May 15, 1954, air force chief of staff general Nathan Twining told reporters that the "best brains in the Air Force" were trying to solve the problem of the flying saucers. "If they come from Mars," Twining said, "they are so far ahead of us we have nothing to be afraid of." However, the general's assurances that a technologically advanced culture would automatically be benign did little to calm an increasingly bewildered and alarmed American public. And on December 24, 1959, after important people and politicians had begun to demand

Briefly, AFR 200-2 made a flat and direct statement that the air force was definitely concerned with the reporting of all UFOs "as a possible threat to the security of the United States and its forces, and secondly, to determine technical aspects involved." In the controversial paragraph 9, the secretary of the air force gave specific instructions that air force personnel were not to release reports of unidentified objects, "only reports…where the object has been definitely identified as a familiar object."

On February 27, 1960, Vice Admiral Rosco H. Hillenkoetter, USN, Ret., former head of the Central Intelligence Agency, startled air force personnel when he released to the press photostatic copies of an air force directive that warned air force commands to regard the UFOs as "serious business." The air force admitted that it had issued the order, but added that the photostatic copy that Hillenkoetter had released to the press was only part of a seven-page regulation, which had been issued to update similar past orders, and made no substantive changes in policy.

The official air force directive indicated the remarkable dual role the air force appeared to play in the unfolding UFO drama. From then on, the unidentified flying objects— sometimes treated lightly by the press and referred to as "flying saucers"—had to be rapidly and accurately identified as serious USAF business. As AFR 200-2 pointed out, the air force concern with these sightings was threefold: "To determine if the object was a threat to the defense of the United States; to assess whether continued research in the matter of flying saucers would contribute to technical or scientific knowledge; to explain to the American people what was going on in their skies."

AFR 200-2 stated that the responsibility for handling UFOs should rest with either intelligence, operations, the Provost Marshal, or the Information Officer—in that order of preference, dictated by limits of the base organization. In addition, it was required that every UFO sighting be investigated and reported to the Air Technical Intelligence Center at Wright-Patterson AFB and that explanation to the public be realistic and knowledgeable. Obviously, in spite of official dismissals, the air force was much aware of the UFOs and was actively investigating.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, retired Marine Corps Major Donald E. Keyhoe charged the U.S. Air Force with deliberately censoring information concerning UFOs. As a director of the National Investigations Committee on Aerial Phenomena (NICAP), Keyhoe regularly repeated his accusations that, while the air force was seriously analyzing UFO data in secret, it maintained a policy of officially debunking saucer stories for the press and ridiculing all citizens who reported sightings.

The official air force response was that the reason for the top secret and classified designations on UFO investigations was solely to protect the identities of those individuals who made reports of mysterious, unidentified "somethings" in the skies. The essence of all research, air force spokesmen insisted, was always released to the communications media. Nothing of national interest was being withheld.

But men like Major Keyhoe and the memberships of numerous additional civilian UFO research groups (of which there were once as many as 50) never accepted the air force's claims of serving the greater public interest by releasing all pertinent details of their studies and investigations. On March 28, 1966, after a saucer "flap" in Michigan, Keyhoe was once again repeating his charges that the Pentagon had a top-level policy of discounting all UFO reports and over the past several years had used ridicule to discredit sightings.

On March 30, 1966, spokesmen for the air force called a press conference to tell the American public that they kept an open mind about UFOs and they categorically denied any "hushing" of saucer reports. In the case of recent Michigan sightings, a spokesman said, "marsh gas" had been pinpointed as the source of colored lights observed by a number of people.

But by 1966, public-opinion surveys indicated that more than 50 million Americans believed in the existence of UFOs. Perhaps in 1947 the majority of men and women had been willing to laugh along with official disclaimers and professional flying saucer debunkers, but 20 years later the UFO climate had become considerably warmer.

DELVING DEEPER

Edwards, Frank. Flying Saucers—Serious Business. New York: Lyle Stuart, 1967.

Fawcett, Lawrence, and Barry J. Greenwood. Clear Intent: The Government Coverup of the UFO Experience. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1984.

Good, Timothy. Above Top Secret—The Wordwide UFO Coverup. New York: William Morrow, 1988.

Hynek, J. Allen, and Jacques Vallee. The Edge of Reality. Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1975.

Story, Ronald D., ed. The Encyclopedia of Extraterres trial Encounters. New York: New American Library, 2001.

DELVING DEEPER

Randle, Kevin D. Project Blue Book—Exposed. New York: Marlowe, 1997.

Ruppelt, Edward J. The Report on Unidentified Flying Objects. New York: Doubleday, 1956.

Steiger, Brad, ed. Project Blue Book: The Top Secret UFO Findings Revealed. New York: ConFucian Press/Ballantine, 1976.

Story, Ronald D., ed. The Encyclopedia of Extraterrestrial Encounters. New York: New American Library, 2001.

DELVING DEEPER

Condon, Edward U. The Scientific Study of Unidentified Flying Objects. New York: Bantam Books, 1969.

Randle, Kevin D. Project Blue Book—Exposed. New York: Marlowe, 1997.

Saunders, David R., and R. Roger Harkins. UFOs? Yes! Where the Condon Committee Went Wrong. New York: New American Library, 1968.

Story, Ronald D., ed. The Encyclopedia of Extraterrestrial Encounters. New York: New American Library, 2001.

DELVING DEEPER

Beckley, Timothy Green. MJ-12 and the Riddle of Hangar 18. New Brunswick, N.J.: Inner Light Publications, 1989.

Berlitz, Charles, and William L. Moore. The Roswell Incident. New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1980.

Friedman, Staton T., and Don Berliner. Crash at Corona. New York: Paragon Books, 1992.

Randle, Kevin D., and Donald R. Schmitt. UFO Crash at Roswell. New York: Avon Books, 1991

Scully, Frank. Behind the Flying Saucers. New York: Henry Holt, 1950.

DELVING DEEPER

Berlitz, Charles, and William L. Moore. The Roswell Incident. New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1980.

Friedman, Staton T., and Don Berliner. Crash at Corona. New York: Paragon Books, 1992.

Korff, Kal K. The Roswell UFO Crash. New York: Prometheus Books, 1997.

Randle, Kevin D. Conspiracy of Silence. New York: Avon Books, 1997.

——. Roswell UFO Crash Update. New Brunswick, N.J.: Inner Light Publications, 1995.

Randle, Kevin D., and Donald R. Schmitt. UFO Crash at Roswell. New York: Avon Books, 1991.

U.S. Air Force. The Roswell Report: Case Closed. June 1997.

DELVING DEEPER

Randle, Kevin D. Conspiracy of Silence. New York: Avon Books, 1997.

——. A History of UFO Crashes. New York: Avon Books, 1995.

Steiger, Brad, ed. Project Blue Book: The Top Secret UFO Findings Revealed. New York: ConFucian Press/Ballantine, 1978.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: