MAGI

Everyone who knows the traditional story of Christmas has heard of the three magi who followed the star in the East and who traveled afar to worship at the manger wherein lay the baby Jesus (c. 6 B.C.E.–c. 30 C.E.). These magi were not kings, but "wise ones," astrologers and priests of ancient Persia, philosophers of Zoroastrian wisdom, and their title has provided the root for the words "magic," "magician," and so forth. Such men were the councilors of the Eastern empires, the possessors of occult secrets that guided royalty.

In Europe during the Middle Ages, those who bore the title of magi were more likely to be men who had devoted their lives to the accumulation of occult wisdom and knowledge from the Kabbalah, the ancient Egyptians, the Arabs, and various pagan sources, and had thereby come under the scrutiny of the church and suspected of communicating with demons. Although these individuals valiantly clung to precious fragments of ancient lore and insisted that they were practitioners of good magic, the clergy saw few distinctions between the magi and the witches that the Inquisition sought to bring to trial for demonolatry and devil worship. It was not until the advent of the Renaissance that the magi and their forbidden knowledge began to gain a certain acceptance among the courts of Europe and the better educated members of the general populace.

Perhaps one of the greatest difficulties that the magi had with the orthodox clergy was their contention that angelic beings could be summoned to assist in the practice of white magick. There were seven major planetary spirits, or archangels, that the magi were interested in contacting: Raphael, Gabriel, Canael, Michael, Zadikel, Haniel, and Zaphkiel. One of the original sources of such instruction allegedly came from the great Egyptian magi and master of the occult, Hermes-Thoth, who described the revelation he had been given when he received a shimmering vision of a perfectly formed, colossal man of great beauty. Gently the being spoke to Hermes and identified itself as Pymander, the thought of the All-Powerful, who had come to give him strength because of his love of justice and his desire to seek the truth.

Pymander told Hermes that he might make a wish and it would be granted to him. Hermes-Thoth asked for a ray of the entity's divine knowledge. Pymander granted the wish, and Hermes was immediately inundated with wondrous visions, all beyond human comprehension and imagination. After the imagery had ceased, the blackness surrounding Hermes grew terrifying. A harsh and discordant voice boomed through the ether, creating a chaotic tempest of roaring winds and thunderous explosions. The mighty and terrible voice left Hermes filled with awe. Then from the All-Powerful came seven spirits who moved in seven circles; and in the circles were all the beings that composed the universe. The action of the seven spirits in their circles is called fate, and these circles themselves are enclosed in the divine Thought that permeates them eternally.

Hermes was given to comprehend that God had committed to the seven spirits the governing of the elements and the creation of their combined products. But because God created humans in his own image, and, pleased with this image, had given them power over terrestrial nature, God would grant the ability to command the seven spirits to those humans who could learn to know themselves, for they were and could come to conquer the duality of their earthly nature. They would truly become magi who learned to triumph over sensual temptations and to increase their mental faculties. God would give such adepts a measure of light in proportion to their merits, and they would be allowed to penetrate the most profound mysteries of nature. Assisting these magi in their work on Earth would be the seven superior spirits of the Egyptian system, acting as intermediaries between God and humans. These seven spirits were the same beings that the Brahmans of ancient India called the seven Devas, that in Persia were called the seven Amaschapands, that in Chaldea were called the seven Great Angels, that in Jewish Kabbalism are called the seven Archangels.

Later, various magi sought to reconcile the Christian hierarchy of celestial spirits with the traditions of Hermes by classifying the angels into three hierarchies, each subdivided into three orders:

- The First Hierarchy: Seraphim, Cherubim, and Thrones

- The Second Hierarchy: Dominions, Powers, and Authorities [Virtues]

- The Third Hierarchy: Principalities, Archangels, and Angels.

These spirits are considered more perfect in essence than humans, and they are thought to be on Earth to help. They work out the pattern of ordeals that each human being must pass through, and they give an account of human actions to God after one passes from the physical plane. They cannot, however, interfere in any way with human free will, which always must make the choice between good and evil. In their capacity to help, though, these angels can be called upon to assist humans in various ways.

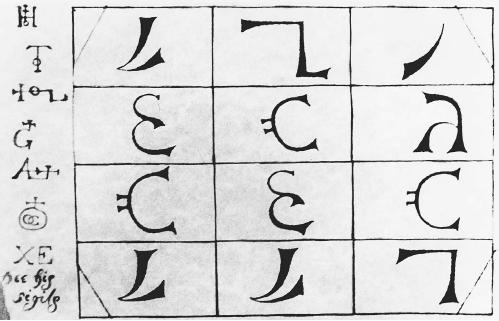

It is these archangels, then, that the magi evoke in their ceremonies. Accompanying the concept of the planetary spirits, or archangels, was something the Egyptians called "hekau" or word of power. The word of power, when spoken, released a vibration capable of evoking spirits. The most powerful hekau for calling up a specific spirit in ceremonial magic is that spirit's name.

"To name is to define," cried Count Cagliostro, a famous occultist of the eighteenth century. And, to the magi of the Middle Ages, to know the name of a spirit was to be able to command its presence, thereby making them true miracle workers.

DELVING DEEPER

Budge, E. A. Wallis. Egyptian Magic. New York: Dover Books, 1971.

Caron, M., and S. Hutin. The Alchemists. Translated by Helen R. Lane. New York: Grove Press, 1961.

Meyer, Marvin, and Richard Smith, eds. Ancient Christian Magic. San Francisco: HarperSanFran cisco, 1994.

Seligmann, Kurt. The History of Magic. New York: Meridian Books, 1960.

Spence, Lewis. An Encyclopedia of Occultism. New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books, 1960.

DELVING DEEPER

Cavendish, Richard. The Black Arts. New York: Capricorn Books, 1968.

Caron, M., and S. Hutin. The Alchemists. Translated by Helen R. Lane. New York: Grove Press, 1961.

De Givry, Emile Grillot. Illustrated Anthology of Sorcery, Magic and Alchemy. Translated by J. Courtenay Locke. New York: Causeway Books, 1973.

Heer, Friedrich. The Medieval World: Europe 1100 to 1350. Translated by Janet Sondheimer. Cleve land, Ohio: World Books, 1961.

Meyer, Marvin, and Richard Smith, eds. Ancient Christian Magic. San Francisco: HarperSanFran cisco, 1994.

Seligmann, Kurt. The History of Magic. New York: Meridian Books, 1960.

Spence, Lewis. An Encyclopedia of Occultism. New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books, 1960.

DELVING DEEPER

De Givry, Emile Grillot. Illustrated Anthology of Sorcery, Magic and Alchemy. Translated by J. Courtenay Locke. New York: Causeway Books, 1973.

Seligmann, Kurt. The History of Magic. New York: Meridian Books, 1960.

Spence, Lewis. An Encyclopedia of Occultism. New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books, 1960.

DELVING DEEPER

Aleister Crowley Foundation. [Online] http://www.thelemicgoldendawn.org/acf/acfl.htm.

Cavendish, Richard. The Black Arts. New York: Capricorn Books, 1968.

Mannix, Daniel P. The Beast. New York: Ballantine Books, 1959.

Rhodes, H. T. F. The Satanic Mass. London: Arrow Books, 1965.

DELVING DEEPER

Caron, M., and S. Hutin. The Alchemists. Translated by Helen R. Lane. New York: Grove Press, 1961.

De Givry, Emile Grillot. Illustrated Anthology of Sorcery, Magic and Alchemy. Translated by J. Courtenay Locke. New York: Causeway Books, 1973.

Seligmann, Kurt. The History of Magic. New York: Meridian Books, 1960.

Spence, Lewis. An Encyclopedia of Occultism. New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books, 1960.

DELVING DEEPER

De Givry, Emile Grillot. Illustrated Anthology of Sorcery, Magic and Alchemy. Translated by J. Courtenay Locke. New York: Causeway Books, 1973.

Seligmann, Kurt. The History of Magic. New York: Meridian Books, 1960.

Spence, Lewis. An Encyclopedia of Occultism. New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books, 1960.

DELVING DEEPER

Arbury, David. "Marie Laveau." Voodoo Dreams. [Online] http://isa.hc.asu.edu/voodoodreams/marie_laveau.asp. 3 March 2002.

Hollerman, Joe. "Mysterious, Spooky, and Sometimes Even a Little Scary." St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb ruary 7, 2002. [Online] http://home.post-dispatch.com/channel/pedweb.nsf/text/86256A0E0068FE5086256B9003E1. 3 March 2002.

"Marie Laveau." Welcome to the Voodoo Museum. [Online] http://www.voodoomuseum.com/marie.html. 3 March 2002.

Metraux, Alfred. Voodoo. New York: Oxford Univer sity Press, 1959.

Steiger, Brad, and John Pendragon. The Weird, the Wild, & the Wicked. New York: Pyramid Books, 1969.

DELVING DEEPER

De Givry, Emile Grillot. Illustrated Anthology of Sorcery, Magic and Alchemy. Translated by J. Courtenay Locke. New York: Causeway Books, 1973.

Seligmann, Kurt. The History of Magic. New York: Meridian Books, 1960.

Spence, Lewis. An Encyclopedia of Occultism. New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books, 1960.

DELVING DEEPER

Meyer, Marvin, and Richard Smith, eds. Ancient Christian Magic. San Francisco: HarperSanFran cisco, 1994.

Seligmann, Kurt. The History of Magic. New York: Meridian Books, 1960.

DELVING DEEPER

De Givry, Emile Grillot. Illustrated Anthology of Sorcery, Magic and Alchemy. Translated by J. Courtenay Locke. New York: Causeway Books, 1973.

Seligmann, Kurt. The History of Magic. New York: Meridian Books, 1960.

Spence, Lewis. An Encyclopedia of Occultism. New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books, 1960.

DELVING DEEPER

Schure, Edouard. The Great Initiates. Translated by Gloria Rasberry. New York: Harper and Row, 1961.

Seligmann, Kurt. The History of Magic. New York: Meridian Books, 1960.

DELVING DEEPER

De Givry, Emile Grillot. Illustrated Anthology of Sorcery, Magic and Alchemy. Translated by J. Courtenay Locke. New York: Causeway Books, 1973.

Seligmann, Kurt. The History of Magic. New York: Meridian Books, 1960.

Skinner, Doug. "The Immortal Count." Fortean Times, June 2001, 40–44.

Spence, Lewis. An Encyclopedia of Occultism. New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books, 1960.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: