Altered States of Consciousness

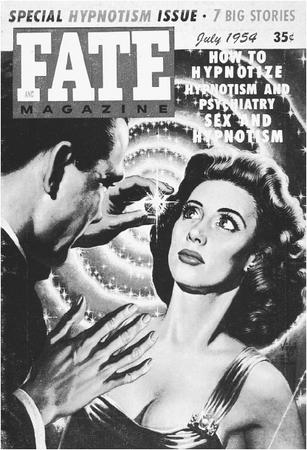

Hypnosis

The process of hypnosis generally requires a hypnotist who asks a subject, one who has agreed to be hypnotized, to relax and to focus his or her attention on the sound of the hypnotist's voice. As the subject relaxes and concentrates on the hypnotist's voice, the hypnotist leads the person deeper and deeper into a trancelike altered state of consciousness. When the subject has reached a deep level of hypnotic trance, the hypnotist will have access to the individual's unconscious.

Many clinical psychologists believe that hypnotherapy permits them to help their clients uncover hidden or repressed memories of fears or abuse that will facilitate their cure. In certain cases, police authorities have encouraged the witnesses of crimes to undergo hypnosis to assist them in recovering details that may result in a speedier resolution of a criminal act. Increasing numbers of clinical or lay hypnotists employ hypnosis to explore cases suggestive of past lives or accounts of alien abductions aboard UFOs. There are also show business hypnotists who induce the trance state in their subjects for the general amusement of their audiences.

Skeptical scientists doubt that hypnosis is a true altered state of consciousness and contend that the people who are classified as good subjects by professional or lay hypnotists are really men and women who are highly suggestible, fantasy-prone individuals. While it may be true that some psychologists and hypnotherapists make rather extravagant claims regarding the powers inherent in the hypnotic state, what actually occurs during hypnosis with certain subjects remains difficult either to define or to debunk.

Throughout the ages, tribal shamans, witch doctors, and religious leaders have used hypnosis to heal the sick and to foretell the future. Egyptian papyri more than 3,000 years old

In the early 1500s, Swiss physician/alchemist Paracelsus (1493–1541) released his theory of what he called magnetic healing. Paracelsus used magnets to treat disease, believing that magnets, as well as the magnetic influence of heavenly bodies, had therapeutic effects. Magnetic treatment theories went through several stages of evolution and many successive scientists. It was during the latter part of the eighteenth century that Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815), acting upon the hypotheses of these predecessors, developed his own theory of "animal magnetism" and hypnosis.

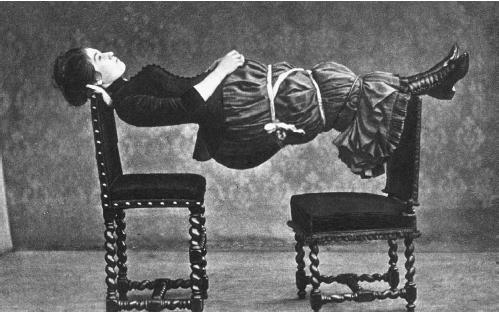

According to Mesmer, hypnosis entailed the specific action of one organism upon another. This action is produced by a magnetic force that radiates from bodily organs and has therapeutic uses. Hypnotism makes use of this force, or the vibrations, issuing from the hypnotist's eyes and fingers.

When Mesmer reintroduced hypnotism to the modern world, paranormal activities and occult beliefs were associated with his works. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, the British Society for Psychical Research appointed a commission for the study of pain transference from hypnotist to hypnotized subject. At the same time, psychologist Edmund Gurney and his assistant Frank Podmore experimented with the same area of research. In the Gurney-Podmore experiments the hypnotist stood behind the blindfolded subject. The hypnotist was then pinched, and the subject told that he would be able to feel the pain in the corresponding area of his own body. Gurney and Podmore reported substantial success, although none of their experiments were carried out with the hypnotist and researcher at any great distance from the subject.

Those earlier psychical researchers were intrigued by the fact that the hypnotic state so closely resembles the state of consciousness in which manifestations of ESP occur. Although a description of the hypnotic state is difficult to achieve, it appears to be much like that somnambulistic state between sleep and waking. Somewhere within this nebulous region, conscious mental activity ceases and deprives the mind of its usual sensory impressions, thereby directing all attention to that one area from which psychic impressions presumably come. To the psychical researcher, there seems scant difference between the trance of a psychic and an individual in the hypnotic state. The only immediately discernible difference is that the one is self-induced, while the other is induced by, and subject to, the control of the hypnotist. The argument therefore presented itself that if ESP can manifest under trance, then why cannot a hypnotist so manipulate the hypnotic state as to achieve the proper state of consciousness and, thereby, literally, induce ESP?

Research continued into the extrasensory aspects of hypnosis, despite hostility from the established sciences. In 1876 Sir William Barrett, an English physicist, presented the results of his experiments in clairvoyant card reading to the British Association for the Advancement of Science. A number of Barrett's colleagues rewarded the physicist's extensive endeavor by walking out during his presentation.

Hypnosis arrived on the threshold of the twentieth century under much the same cloud that had covered it since Mesmer's day; and, in spite of decades of research and experimentation, the great majority of scientific researchers maintain a solid skepticism toward hypnosis at the dawn of the twenty-first century.

The Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scales, a scientific yardstick by which to measure the phenomenon of hypnosis, was developed in the late 1950s by Stanford University psychologists Andre M. Weitzenhoffer and Ernest R. Hilgard. Scoring on the Stanford scales ranges from 0 for those individuals who do not appear to respond to any hypnotic suggestions, to 12, for those who are assessed as extremely responsive to hypnosis. Most people,

Among the results of the studies of Weitzenhoffer and Hilgard were demonstrations that a person's ability to be hypnotized is unrelated to his or her personality traits. Earlier suggestions that those individuals who could be hypnotized were gullible, submissive, imaginative, or socially compliant proved unsupported by the data. People who had the ability to become absorbed in such activities as reading, enjoying music, or daydreaming did appear to be the more hypnotizable subjects.

Another objection by the skeptics that the process of hypnosis was simply a matter of the subject having a vivid imagination also proved to be a false assumption. Many highly imaginative people tested by the experimenters proved to be bad hypnotic subjects, and there appears to be no relation between the ability to imagine and the ability to become a good hypnotic subject.

The Stanford experiments also learned that hypnotized subjects were not passive automatons who would obey a hypnotist's commands to violate their moral or cultural ideals. Instead, the subjects remained active problem solvers while responding to the suggestions of the hypnotist.

By using hypnosis, the scientists at Stanford were able to create transient hallucinations, false memories, and delusions in some subjects. By using positron emission tomography, which directly measures metabolism, the researchers were able to determine that different regions of a subject's brain would be activated when he or she was asked simply to imagine a sound or sight than when the subject was hallucinating under hypnotic suggestion.

The mechanisms by which the process of hypnosis can somehow convince certain subjects not to yield to pain remain a mystery. Many researchers theorize some hypnotic subjects and experienced meditators can allow the altered state of consciousness to bring about an analgesic effect in brain centers higher than those that register the sensations of pain. A 1996 National Institutes of Health panel assessed hypnosis to be an effective method of alleviating pain from cancer and other chronic conditions. Numerous clinical studies demonstrated that hypnosis could also reduce acute pain faced by pregnant women undergoing labor or the pain experienced by burn victims. In some instances, it was judged that hypnosis accomplished greater relief than such chemical pain killers as morphine.

While such experiments certainly indicate that something is going on within a subject's mind during the process of hypnosis, many psychologists, such as Dr. Nicholas Spanos, argue that hypnotic procedures merely influence behavior by altering a subject's motivations, expectations, and interpretations. Such influences have nothing to do with placing a person into a trance or exercising any kind of control over that person's unconscious mind. Hypnosis, in Spanos's view, is an act of social conformity, rather than a unique state of consciousness. The subject, he maintains, is only acting in accordance with the hypnotist's suggestions and responds according to the expectations of how a hypnotized person is supposed to behave.

Critics of hypnotic procedures during police investigations are concerned that too many law enforcement officers consider hypnosis as a kind of magical way to arrive at the truth of a case. The American Society of Clinical Hypnosis has certified about 900 psychologists, only five of whom specialize in forensic hypnosis and assist in police work. Federal courts and about a third of the state courts allow testimony of hypnotized individuals on a case-by-case basis.

Dr. William C. Wester, a nationally recognized psychologist, has used hypnotism to assist victims and witnesses of crimes to remember the details of more than 150 cases. Wester agrees that hypnosis is not magic, but maintains that it is an effective tool in police work. "Hypnosis doesn't always lead to an arrest," Wester told Janice Morse of The Cincinnati Enquirer in 2002. "But it almost always generates some additional investigative leads for the police to follow."

Since 1991, Wester and John W. Kilnapp, a special agent and forensic artist with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, have teamed up to work on more than 50 robberies, rapes, kidnappings, and murders nationwide. After Wester has hypnotized a witness or victim of a crime and assisted that person to describe minute details of the events, Kilnapp works on a composite sketch of the perpetrator of the crime. While the team of artist and psychologist admitted that it was the police who solved the crimes, they estimated that in 95 percent of their cases, they helped expand a brief description of a suspect to fill several pages for investigators to use.

The Society for Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis has stated that hypnosis should not stand alone as the sole medical or psychological treatment for any kind of disorder, but the society suggests that there is strong evidence that hypnosis may be an effective component in the broader treatment of many physical problems and in some conditions may increase the effectiveness of psychotherapy. While the clinical use of hypnosis has not become an accepted means of treatment among medical personnel and psychologists, it has gained many scientific supporters and evolved greatly from its occult and superstitious roots.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: