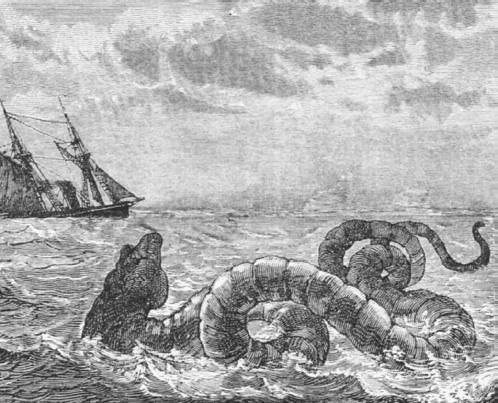

Monsters of Land, Sea, and Air

Sea serpents

"Any fool can disbelieve in sea serpents," commented Victoria, British Columbia, newspaper editor Archie Willis in 1933. Willis's pronouncement came as a sharp rejoinder to the skeptics who laughed at the hundreds of witnesses who swore that they had seen a large snakelike creature swimming in the waters off the coast of the Pacific Northwest. Willis christened the sea monster "Cadborosaurus," and the nickname stuck.

The creature with its long serpentine body, its horselike head, humps on its back, and its remarkable surface swimming speed of up to 40 knots, has been a part of coastal lore from Alaska to Oregon for hundreds of years. While the waters of the Pacific Northwest border one of the deepest underwater trenches on the planet—where almost any massive seabeast could reside—the greatest number of sightings of Cadborosaurus have occurred in the inland waters around Vancouver Island and the northern Olympic Peninsula.

In Cadborosaurus: Survivor of the Deep (2000), Vancouver biologist Dr. Edward L. Bousfield and Dr. Paul H. Leblond, professor of oceanography at the University of British Columbia, describe the creature as a classic sea monster with a flexible, serpentine body, an elongated neck topped by a head resembling that of a horse or giraffe, the presence of anterior flippers, and a dorsally toothed or spiky tail.

When the crew of the yacht Valhalla sighted a sea monster off Parahiba, Brazil, on December 7, 1905, it was fortunate to have among its passengers E. G. B. Meade-Waldo and Michael J. Nicoll, two expert naturalists, Fellows of the Zoological Society of Britain, who were taking part in a scientific expedition to the South Atlantic and Indian Ocean. Meade-Waldo prepared a paper on the sighting, which he presented to the society at its meeting on June 19, 1906. In his report, he told how his attention was first drawn to a "large brown fin…sticking out of the water, dark seaweed-brown in color, somewhat crinkled at the edge." The creature's fin was an astonishing six feet in length "and projected from 18 inches to two feet from the water." Under the water and to the rear of the fin, the zoologist said that he could perceive "the shape of a considerable body. A great head and neck did not touch the [fin] in the water, but came out of the water in front of it, at a distance of certainly not less than 18 inches, probably more. The neck appeared to be the thickness of a slight man's body, and from seven to eight feet was out of the water."

The head, according to Meade-Waldo's expert observation, had a "very turtlelike appearance, as had also the eye…it moved its neck from side to side in a peculiar manner; the color of the head and neck was dark brown above and whitish below." Meade-Waldo also stated that since he saw the creature, he has reflected on its actual size and concluded that it "was probably considerably larger than it appeared at first."

Nicoll discussed the incident of the Valhalla sea monster sighting two years later in his book Three Voyages of a Naturalist: "I feel certain that [the creature] was not a reptile…but a mammal. The general appearance of the creature, especially the soft, almost rubberlike fin, gives one this impression."

Off shore on the Atlantic seacoast of North America, there is a sea serpent that has been paying periodic visits to the Cape Ann area and Gloucester, Massachusetts, for more than 340 years. An Englishman named John Josselyn, who was returning to London, made the first sighting of the creature as it lay "coiled like a cable" on a rock at Cape Ann. Seamen would have killed the serpent, but two Native American crew members protested such an act, stating that all on board would be in danger of terrible retribution if the sea creature was harmed.

On August 6, 1817, Amos Lawrence, founder of the mills which bore his name,

On that same August day, a group of fishermen spotted the marine giant near Eastern Point and shouted that it was making its way between Ten Pound Island and the shore. They said later that they could clearly see the thing's backbone moving vertically as it appeared to be chasing schools of herring around the harbor. Shipmaster Solomon Allen judged the serpent to be between 80 and 90 feet in length.

Generations of Gloucester residents and tourists have sighted the Cape Ann sea serpent, often as they sailed the harbor and nearly always stating that they were frightened by the appearance of a huge snakelike creature at least 70 feet in length.

In April 1975, some fishermen saw the monster up close and personal and were able to provide one of the more complete descriptions of the monster.

According to Captain John Favazza, they had sighted a large, dark object on their starboard side, about 80 feet away, that they had at first thought was a whale. Then a serpent-like creature lifted its head from the surface, saw the fishing boat, and began to swim directly toward them. Favazza later told reporters that the sea serpent was black, smooth rather than scaly, with a pointed head, small eyes, and a white line around its mouth. It swam sideways in the water, like a snake. It was longer than his 66-foot boat, and he estimated its girth as about 15 feet around.

Some cryptozoologists, individuals who study the possibility of such creatures as sea and lake monsters truly existing, have theorized that plesiosaurs, one of the giant reptiles of the Mesozoic Age, which ended about 70 million years ago, could have survived in the depths of the relatively unchanged environment of Earthl's oceans. Because some sea monster sightings occur in cold waters, other researchers favor the survival of an ancient species of mammals, such as the ancestor of the whale known as Zeuglodon or Basilosaurus. The Basilosaurus had a slim, elongated, snakelike body measuring more than 70 feet in length which the huge creature propelled by means of a single pair of fins at its forward end.

The debate over what monstrous creatures best wear the mantle of "sea monster" could have been solved for all time back in 1852 when two New Bedford whaling vessels, the Monongahela and the Rebecca Sims, were drifting slowly in the Pacific doldrums, their sails limp from lack of wind. When the lookout's shout of "something big in the water" caused Captain Seabury of the Monongahela to use his telescope to view the object; he could distinguish only a huge living creature, thrashing about in the water as if in great agony. The captain's immediate deduction was that they had come upon a whale that had been wounded by the harpoons of another whaler's long-boats and was now dying.

Seabury ordered three longboats over the side to end the beast's pain, and he was in the first boat as it pulled alongside the massive thing that he still believed was a wounded whale. The instant a harpoon struck the beast, a nightmarish head 10 feet long rose out of the water and lunged at the boats. Two of the long-boats were capsized in seconds. Before the monster submerged, the terrified whalers realized at once that they were dealing with a sea creature the likes of which they had never seen.

Unfurling her sails to catch what little wind there was, the Monongahela managed to come alongside the capsized longboats and began to pick up the seamen who were bobbing in the water, fearing that the hideous beast might at any moment resurface and eat them. The Rebecca Sims, under the command of Captain Gavitt, pulled alongside her sister ship, and the crews of the two ships began discussing the strange monster that they had encountered.

The next morning, the crewmen had pulled in only about half of the line when the massive carcass suddenly popped to the surface. It was much greater in length than the ship, which measured 100 feet from stem to stern, and it had a thick body that was about 50 feet in diameter. Its color was a brownish gray with a light stripe about three feet wide running its full length. Its neck was 10 feet around, and it supported a grotesque head that was 10 feet long and shaped like that of a gigantic alligator. The astounded crewmen counted 94 teeth in its ghastly jaws—and each of the three-inch, saberlike teeth were hooked backward, like those of a snake.

Seabury was fully aware of the ridicule accorded to sailing masters and their crews who claimed to have encountered "sea serpents," so he gave orders that the hideous head be chopped off and placed in a huge pickling vat in order to preserve it until they returned to New Bedford. In addition, he wrote a detailed report of their harpooning the sea monster and he provided a complete description of the thing. Since Gavitt and his crew were homeward bound, Seabury gave him the report in order to prepare New Bedford for the astonishing exhibit that he and his men would bring with them upon their own return.

If only Seabury would have transferred the grisly head to Gavitt's vessel along with his report of the monster, the doubting world would have had its first mounted sea serpent's head more than 150 years ago. Captain Seabury's account of the incredible sea serpent arrived safely in New Bedford and was entered into the records along with the personal oath of Captain Gavitt. But the Monongahela never returned to port with its incredible cargo. Years later her nameboard was found on the shore of Umnak Island in the Aleutians.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: