Christian Mystery Schools, Cults, Heresies

Gnosticism

Several cults with widely differing beliefs all bearing the label of "Gnostic" arose in the first century, strongly competing with the advent of Christianity. The term Gnostic is derived

Many of the Gnostic sects blended elements of Christianity with the Eleusianian mysteries, combining them with Indian, Egyptian, and Babylonian magic, and also bringing in aspects of the Jewish Kabbalah as well. Whatever the expression of the various Gnostic belief structures, they all emphasized a detachment from the material world and an elaborate series of spiritual hierarchies through which those initiates who had achieved personal knowledge of divinity could arise. The Christian Church Fathers branded the Gnostics as heretics just as soon as they had developed enough power within the Roman Empire to do so, and the cult continued to be anathema to the Church down through its variations in the Cathars, the Albigensis, and the Knights Templar.

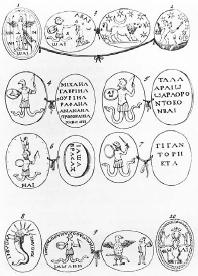

The first Gnostic of importance would seem to be Simon Magus (fl. c. 67 C.E.), a Samarian sorcerer, a contemporary of the apostles, who was converted to Christianity, then strongly rebuked by Peter when he sought to purchase the wonder-working power of the Holy Spirit (Acts 8:9–24). Those Gnostic Christians influenced by such charismatic individuals as Simon Magus believed that there was a secret oral tradition that had been passed down from Jesus that had much greater power and authority than the scriptures and epistles offered by the orthodox teachers of Christianity. The Gnostics, like the initiates of the Greek and Egyptian mysteries, sought direct experience with the divine and they believed that this communion could be achieved by uttering secret words of wisdom that God had granted to specially enlightened teachers. The Gnostics considered themselves much more spiritually advanced than the larger community of Christians, whom they regarded as ignorant plodders and easily led sheep.

Nearly everything that was known about the Christian Gnostics prior to the discovery of the Nag Hammadi library in 1945 was taken from the highly prejudiced writings of such Church Fathers as Irenaeus, Hippolytus, and Epiphanius, who condemned the Gnostics as heretics and devil-worshippers. The library that was found in Upper Egypt consists of 12 books, plus eight leaves removed from a thirteenth book and tucked inside the front cover of the sixth. These eight leaves make up the complete text of a work that has been taken out of a volume of collected works. Each of the books, except the tenth, consists of a collection of brief works, such as "The Prayer of the Apostle Paul," "The Gospel of Thomas," "The Sophia of Jesus Christ," "The Gospel of the Egyptians," and so on. Although the Nag Hammadi library is written in Coptic, the texts were originally composed in Greek and contain many references to Egyptian sites and beliefs. And although the work is ascribed to Christian Gnostics, there are many essays within the library that do not seem to reflect much of the Christian tradition. While there are references to a Gnostic Savior, his presentation does not seem to be based on the Jesus found in the New Testament. On those occasions when Jesus does appear in the texts, he often appears to be criticizing those orthodox Christians who have confused his words and his teachings. By following the true way and thus achieving transcendence, Jesus says in "The Apocalypse of Peter," every believer's "resurrection" becomes a spiritual reality.

Throughout the Nag Hammadi library there are admonitions to resist the lures and traps of trying to be content in a world that has been corrupted by evil. The world created by God is good. The evil that has permeated the world, although alien to its original design, has risen to the status where it has become the ruler of Earth. Rather than perceiving existence as a battle between God and the devil, the Gnostics envisioned a struggle between the true, most high, unknowable God and the lesser god of this Earth, the "Demiurge," that they associated with the angry, jealous, rule-giving deity of the ancient Hebrews. They believe that all humans have the ability to awaken to the realization that they have within themselves a spark of the divine. By attuning to the mystical awareness within them, they may transcend all earthly entrapments and regain their true spiritual home. Jesus had been sent by God as a guide to teach humans how to free themselves from the control of the Demiurge and to understand

As if the theology of the Gnostics was not enough to have them branded as heretics by the orthodox Christian establishment, their doctrines and their scriptural texts often utilized feminine imagery and symbology. Even more offensive to the patriarchal Church Fathers was the Gnostic assertion that Jesus had close women disciples as well as men. In The Gospel of Phillip it is written that the Lord loved Mary Magdalene above all the other apostles, and he sharply reprimanded those of his followers who objected to his open displays of affection toward her.

Gnosticism ceased to be a threat to the organized Christian Church by the fourteenth century, but many of its tenets of belief have never faded completely from the thoughts and writings of many scholars and intellectuals down through the centuries. Elements of the Gnostic creeds surfaced again in the New Age movement of the late twentieth century. An impetus to study the writings of the Gnostic texts was provided by psychologist Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961), who perceived value in the writings of Valentinus, a prominent Gnostic teacher. In Jung's opinion, Gnosticism's depiction of the struggle between God and the false god represented the turmoil that existed among various aspects of the human psyche. God, in the psychologist's interpretation, was the personal unconscious; the Demiurge was the ego, the organizing principle of consciousness; and Christ was the unified self, the complete human.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: