Tribal Mysteries

Ghost dance

In 1890 Jack "Wovoka" Wilson (1856–1932), a Paiute who worked as a ranch hand for a white rancher, came down with an illness accompanied by a terrible fever. For three days, the Native American lay as if dead. When he returned to consciousness and to the arms of his wife Mary, he told the Paiute who had assembled around his "dead" body that his spirit had left his body and had walked with God, the Old Man, for those three days. As if that were not wonder enough, the Old Man had given him a powerful vision to share with the Paiute people.

Wovoka's vision had revealed that Jesus (c. 6 B.C.E.–c. 30 C.E.) moved again upon the Earth Mother and that the dead of many tribes were alive in the spirit world, just waiting to be reborn. If the native people wished the buffalo to return, the grasses to grow tall, the rivers to

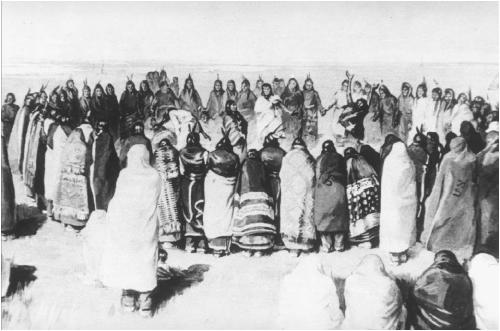

The most important part of the vision that God gave to Wovoka was how to perform the Ghost Dance. The Paiute prophet told his people that the dance had never been performed anywhere on Earth. It was the dance of the spirit people of the Other World. To perform this dance was to insure that God's blessings would be bestowed upon the tribe, and many ghosts would materialize during the dance to join with the living in celebration of the return of the old ways. Wovoka said that the Old Man had spoken to him as if he were his son, and God had assured him that many miracles would be worked through him. In his heart and in his life, Wovoka, also known in his tribe as "the Cutter," became Jesus; Mason Valley, Nevada became Galilee; and the Native American people received a messiah.

Wovoka's father had been the respected holy man Tavibo and his grandfather had been the esteemed prophet Wodziwob. And now he, too, had spent his time in imitation of death, lying in a trance-like state for three days, receiving his spiritual initiation in the Other World. Wovoka had emerged as a holy man and a prophet, and history would forever know him as the Paiute Messiah.

Soon, many representatives from various tribes visited the Paiute and saw them dance Wovoka's vision. They saw the truth of the Ghost Dance, and they began calling Wovoka, Jesus. His fame spread so far that newspaper reporters from St. Louis, New York, and Chicago came to see the Ghost Dance Messiah and record his words. Whites were pleased that Wovoka did not speak of war, only of the importance of all people living together in harmony.

Chief Big Foot (1825?–1890) of the Sioux traveled from the camp in South Dakota to Nevada to see the Ghost Dance, and he returned to tell Sitting Bull (c. 1831–1890) about Wovoka's promise that the dead from many tribes would soon be joining the living in a restored world that would once again be filled with plentiful game, herds of buffalo, and the tall grasses of the prairie. All those whites who interfered with this would be swallowed up by the earth, and only those who practiced the ways of peace would be spared.

Sitting Bull, the great Sioux prophet and holy man, was impressed by Big Foot's report, but rather noncommittal toward the teachings of the Paiute Messiah. While he did not wholeheartedly endorse the Ghost Dance, neither did he prevent those Sioux who wished to join in the ritual from doing so.

Sometime during the fall of 1890, the Ghost Dance spread through the Sioux villages of the Dakota reservations with the addition of the Ghost Shirts, special shirts that could resist the bullets of the bluecoats, the soldiers who might attempt to stop the rebirth of the old ways. As the Sioux danced, sometimes through the night, believing they were hastening the return of the buffalo and their many relatives who had been killed in combat with the pony soldiers, the settlers and townsfolk in the Dakota territory became anxious. And when the Sioux at Sitting Bull's Grand River camp began to dance with rifles, it becme apparent to the white soldiers that the Ghost Dance was really a war dance after all.

After a nervous Indian agent at Pine Ridge wired his superiors in Washington that the Sioux were dancing in the snow and were acting crazy, it was decided that Sitting Bull and other Sioux leaders should be removed from the general population and confined in a military post until the fanatical interest in the Ghost Dance religion had subsided. Sitting Bull was killed by Sioux reservation police on December 15, 1890, and Big Foot and 350 of his people were brought to the edge of Wounded Knee to camp.

On December 28, Sioux police, Fouchet's Cavalry, and Drum's Infantry moved against the Sioux camp at Grand River. The aggressors also brought with them Hotchkiss multiple-firing guns and mountain howitzers. A shot rang out. The Sioux scattered to retrieve rifles that had been discarded or hidden. From all around the camp, fire from the automatic rifles, violent eruptions from the exploding shells, and volleys of bullets destroyed the village. As they were being slaughtered by two battalions of soldiers, the Sioux sang Ghost Dance songs, blended with their own death chants. Within a short period of time, approximately 300 Sioux had been killed, Big Foot among them, and 25 soldiers had lost their lives. The massacre at Wounded Knee ended the Native American tribes' widespread practice of the Ghost Dance religion and ended the Indian Wars.

It was said that Wovoka wept bitterly when he learned the fate of the Sioux at Wounded Knee. Jack Wilson, the Cutter, the Paiute Messiah, died in 1932.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: